COMEL AWARD VANNA MIGLIORIN 20-21

Aluminium in the Art of the ‘900: Conversation with Elena Pontiggia

Aluminium in the art of the ‘900: homage to Regina Bracchi

As a side event to the Aluminum Bonds exhibition, which sees the 13 finalist works of the eighth edition of the COMEL Vanna Migliorin Contemporary Art Award on display, last October 7 the meeting with the art historian and academic, as well as a member of the jury of this edition of the COMEL Award, Elena Pontiggia took place.

The professor, one of the world’s leading academics of art between the two wars, held an in-depth conversation on the combination of art and aluminium, focusing on the early twentieth century and talking about an artist of great interest: Regina Bracchi.

Elena Pontiggia began by confessing her appreciation for the city of Latina “Latina is an open-air museum. In Italy in particular, but also throughout the world, there are a certain number of cities that are open-air museums, but they are all ancient. There are very few contemporary cities created in the 1900s that have become open-air museums and among these very few, your city is at the very first position … coming to Latina for a scholar of art between the two wars is the experience of seeing the things you loved the most. It’s not the first time I’ve come, but coming back is always a great emotion “.

We then got to the heart of the theme with the interesting definition of sculpture which for Professor Pontiggia is the most difficult kind of art: “… not without a reason Barnett Newman, the American painter, said ‘it’s that thing one stumbles upon when you go to see the paintings’. Sculpture does not caress the eye with color, it is more difficult than painting, less spectacular, less understandable. It is more difficult to organize sculpture exhibitions, due to transport and costs, fewer sculpture exhibitions are held … So the research concerning this fundamental art is doubly blessed! “.

With the avant-garde of the twentieth century, the idea of sculpture and above all the materials used changed: “The Modern – says Professor Pontiggia – has cultivated a different idea of materials: less celebration and more emotion. Aluminium has many qualities, among these, there is lightness and therefore lyricism rather than monumentalism. Despite being a material that has its own remarkable strength, it suggests an idea of lightness, brightness and therefore it was particularly loved by our avant-gardes “.

As Elena Pontiggia pointed out, in Italy the interest in aluminium has spread above all in the futurist field, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti already in the manifesto Uccidiamo il Chiar di Luna (1909) affirmed: “the importance of aluminium as a new and modern material, as a luminous and light material… Aluminium is above all light, and therefore it is an antimatter material due to its luminosity ”. Marinetti, therefore, hoped for the overcoming of nineteenth-century sentimental rhetoric for new and modern art, hence the reason why futurists had such a strong propensity for the use of aluminium: “Futurism – Pontiggia affirms – which is that trend that has above all sought the new, the modern, which opposed the repetitive cult of the ancient, not the love for the ancient as such, but the cult, the professorial dogmatism towards the ancient. Futurism, which saw everything as a movement, as a fall in love with the future, had as its law the search for materials other than traditional ones “.

“Aluminum – continues the scholar – is identified as a material of the future for light and lightness … that vital lightness, which has nothing rhetorical, a modern lightness. Also speaking of poetry (Manifesto of aeropoetry ) Aluminum is mentioned. Marinetti loved this material so much that he felt all its modernity ”.

After the passionate introduction, Professor Pontiggia showed the audience a series of futurist aluminium sculptures that demonstrate how research into sculpture was revolutionary and in search of new definitions. An example among the many proposed is

The Violinist (1921) by Thayaht (in the world Ernesto Michahelles), in which we see “a kind of mantle that binds the figure and the musical instrument together as if it were a note, a whole so harmonious, which gives us the idea of who the violinist, the musician or the artist is, and what we are art lovers are too: we are all in one with what we love, in this case with music “.

The mention of the condition of artists and in particular of sculptors was also very compelling “in the Thirties for a woman to work as an artist was particularly difficult, in part it is still today, but back then it was even more so. I remember that a great artist Felicita Frai told me that it was difficult to be an artist because no one took you seriously. It is true that in the nineteenth-century girls were taught to paint, model, embroider or play the piano. That wasn’t artistic research, it was a parlor exercise. It is evident that when we were faced with women artists, with the legacy of this education of girls from a good family, we thought ‘we are not in front of a true artist who struggles to try to achieve something and express himself, but we find ourselves in front of a polite exercise of a girl from a good family. So we carried this prejudice with us ”.

Finally, Regina Bracchi came: “She was born in the Po Valley – says the professor – in 1921 she moved to Milan and married a painter and fortunately she had his support, that was so rare for women of the time. She approached futurism but her being a futurist was very “sui generis”. She said ‘I am a futurist because I am allergic to every rule and imposition of common poetics and law. Futurists are free and independent so I want to be a futurist ‘. In fact, there is not much Futurism in her work, but she ironically said ‘I’m a futurist because I do what I want “.

In 1934 she signed the manifesto of Aeroplastica, a futurist sculpture inspired by flight and she also joined the MAC in the large abstract art movement that was formed in Milan in 1948.The professor showed the public a series of works created by Regina Bracchi who preferred aluminium among the various materials, sculptures that are characterized by grace, simplicity, and acute observation of reality, of people, of feelings beyond the wise use of materials.

Among her most famous works, the most representative is the Danzatrice (1930) in which Regina “took this aluminium sheet and succeeded giving the idea of a sense of movement, truly futurist, and was able to suggest the movement of the dancer, which is not like the movement of grace of Degas dancers, but a movement of ease. This movement, on a closer inspection, has nothing to do with the real movements of the tutu dancer but is an almost delightfully clumsy movement, in which the dancer hovers like a dragonfly in the air. It is an example of freedom, of fluency, of agility of pleasure to move rather than the very rigid canon of traditional classical dance “.

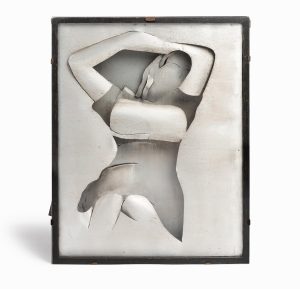

Of great interest, among the various works shown by Elena Pontiggia, there is certainly L’Amante dell’Aviatore, in this sculpture

“you can see how Regina worked – explains the scholar – she took an aluminum sheet, and through a game of voids and full represented the figure. The idea of the aviator’s lover was very beautiful: which had not occurred to any man artist, all the futurist sculptors involved in depicting flight scenes had never thought of representing an aviator’s lover. Perhaps a feminine sensibility was needed, but in reality, it is not only the woman in love with the aviator, we are all lovers of aviators, we – as Montale would say – the race of those who remain on the ground, we who are not artists but love the art, we who do not do great things but are in love with those who do great things, so we are all dreamers in the armchair, who love and observe beautiful things even if we are not destined to do them. This thoughtful figure who indulges go to daydreams, nostalgia, desire, left at home, sitting is an image of our life too, and this is how Regina represents it. From a stylistic point of view, the transition to two-dimensionality is important: from a sculpture that is volume and space to a sculpture that is no longer space but surface, virtuality, spatial abstraction. Beyond these stylistic innovations, the most engaging aspect of her Regina’s work is her poetry “.

An exciting, enlightening meeting on issues that are still little studied and in-depth that make us understand how much there is still to learn about the century that has just passed. And it is the culture, but also the passion and enthusiasm of scholars such as Elena Pontiggia that will make it possible to understand contemporary art, the daughter of those avant-gardes, always too little understood and appreciated.