VINCITRICE PREMIO COMEL DELLA GIURIA 2022

Interview with Chiara A. Colombo

di Ilaria Ferri

Chiara A. Colombo was born in Monza in 1963, she graduated in painting from NABA in Milan in 1987. Her artistic research develops from the sign as an element that investigates the subtle boundary between painting and sculpture. From almost abstract initial themes, Architecture, Clouds, and Angels, over time she has turned towards a more committed dimension in a social and ecological key without losing, even in this context of realism, the lyricism, and lightness that are the stylistic code of her work. She is an incessant experimenter with materials, she often uses natural elements and textile and metal waste from industrial production to create sculptures and paintings. Reflecting on the work of F. Goya, she created drawings, sculptures, and calcography engravings on the theme of the death penalty, sometimes in relation to news stories – such as the story of the nine Ogoni activists in Nigeria in 1995, the genesis of the installation “Impiccati” (Hanged).

You stated that the work Betulle (winner of Endless Aluminium the 9th edition of the COMEL Award), although part of a larger project, was created specifically for the Award. It is a work that, starting from a fine cinematic quotation (Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Childhood of Ivan – 1962), deals with the theme of war, and the cyclical nature of certain conflicts contrasted with the immutable and endlesscyclical of Nature, which impassively observes the horrors produced by Man. A juxtaposition which is not only conceptual but also formal. Tell us about this beautiful work. How did the idea of entering it for the COMEL award come from?

I made the work Betulle specifically for the COMEL Award 2022 by reworking an idea that “in nuce” (briefly) and also as a technique I had experimented with, for a work presented at the MAC in Lissone in 2009 with the significant title “Crimea.” Betulle, then, is also a reflection on war, a reflection which is not purely related to the recent and nearby Russian-Ukrainian one: in the foreground lies the solitary silhouette of a soldier and in the background a birch forest with its monotonous procession of vertical lines silently comments on his death. My interpretation of the theme of the competition, “Artist can only be one who has his own religion, an original insight into infinity” is not related to mathematical infinity but to the endless existence of Nature, to the contrast between the infinity of Nature’s cycle, the source of life and well-being, and the infinity of the horrors of History. The nature watches motionless, a silent but ever-present spectator to the dramatic events of the history. This idea also stems from the suggestion of Tarkowsky’s film, “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962) in which the tragic events of World War II narrated are punctuated by the birch forest that characterizes the Russian-Ukrainian environment in which they take place.

I was struck by how much A. Anniballi has written about the forest in the film “that enchanted forest that still and always represents the possibility of clinging to a remnant of beauty in order to rediscover, if only for a moment, the sense of existing beyond all war.” The above juxtaposition is also highlighted by the technique of “Birches”. The thin sheet of aluminium is scratched, raped by dry point etchings and hammer blows that move the surface creating reliefs. Oil colour intervenes to delicately detect the mark and, in some areas, produces blue-green and brown highlights. The colour does not hide the surface metal, which, camping intact in much of the space, dramatically heightens the sense of absence relative to the subject depicted. This emptiness also partly highlights the role of the viewers and the environment, which, like moving shadows, are reflected on the semi reflecting aluminium, giving changing shapes to the painting.

The work, which also has a narrative value, is part of a series that I intend to present complete in the solo exhibition at Spazio COMEL in Latina in May. My works can often be read both in autonomously and as part of a whole, as individuals in a social group.

Viaggio del sole, 1990 – mixed media on paper frame and sculpture of willows and steel

You use a variety of materials in your works, from textile and metal scraps from manufacturing industry to natural elements. In particular, aluminium is one of the materials you use the most, what is your relationship with this metal? What does it mean to you to participate in a competition focused on a material that is so dear to you?

I began my artistic journey in three-dimensionality using materials found in nature, willow branches to which I added small metal scraps. I later made my signs sculptural with tubular aluminium elements, joined by interlocking or riveted, as in the installation “Sedie for the exhibition in the garden of Villa Braila in Lodi, 2004, also reproposed in the space interior of the Monza station’s royal lounge. The chairs, about 250 cm high, and the ghostly figures that appear in some, are linear and light sculptures like profiles that do not impose themselves in the space with mass but, thanks to the luster of the material, have considerable visibility in the context.

In 2009 I began instead to use raw aluminium sheets as thin as sheets of paper but, unlike unlike this, resistant, and able to withstand incisions and tears. For the exhibition “Presences of the Contemporary” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lissone, 2009 I made a work (cm200x200) entitled “Crimea” where I addressed the theme of war later taken up in the work “Birch trees” created for the 9th edition of the COMEL Award 2022.

In fired aluminium, worked with softer and more plastic movements, I made giant and fantastic, sculptural reworkings of childhood drawings, for the exhibition at the Belvedere of the Villa Reale in Monza in December 2021.

Given the non-occasionality therefore of the use of aluminium in my artistic research, the award given to me by such an influential jury fills me with joy and consolidates me on the path I have taken.

Sedie, 2004 – Aluminium. Detail of the installation of Villa Braila, Lodi

In your works there is always a reference to foundational themes, to news events related to the suppression of human rights or the inequity of violence. How important is it for you to tell through art what affects you, what shakes your soul? Does art in your opinion have to have a social and pedagogical value or is it more simply a catalyst for related sensibilities?

When I was young, I did years of volunteer work with marginalized or disabled kids and militated in anti-militarist groups. I have kept alive this sensitivity and attention to the dramas of our time, which I express not through direct action but through the visual language of art.

In my works, the fact is never directly or crudely depicted. There is always a poetic reworking, and not because the death penalty or war can be in any way positive but because these situations, which seem to monotonously characterize human existence, should be pondered in silence.

For me, art is this way of reflecting and reframing things that I do not understand and that disturb me, such as the fact that in such a wealthy society there are people who are starving in the cold or have to live on the streets, on the ground, in general indifference. The charcoal drawings of the homeless are made on photos taken by me at night in the wealthy streets of downtown Milan.

You often cite Calvinian lightness, which you faithfully apply in your works: to important, often somber themes (such as mental illness, war, and others) you counterpose a lyricism, the lightness of strokes, forms as well as composition in both your paintings and installations and sculptures. How does this need arise both thematically and compositionally?

“One must be as light as a bird, not as a feather,” said P. Valery and Italo Calvino in his American Lectures, “There is a lightness of thoughtfulness… Lightness for me is associated with precision and determination, not with vagueness and abandonment to chance.” That is, lightness does not mean indecision or fragility.

Clement Greenberg wrote, “Picasso sees the painting as a wall, Klee as a page. I have the same gaze as Klee”. My page is layers of tissue paper, an aluminium foil half a millimetre thick, a thin trace. In my works, the shadow often has a greater sense of reality and concreteness than the thing that generates it. Lightness is not an escape from reality and the tragedies that characterize it but is the ability not to be terrified and suffocated by it. Lightness is a property of air, of light, of breath, it is going upward as a form of hope. The problem of the seriousness of some situations of injustice lies not in the physical, or material impossibility of solving them but in the mental impossibility of featuring out the solution. Therefore, art can play an effective political action more than powerful men by working on the change of horizon, on the refinement of sensibility.

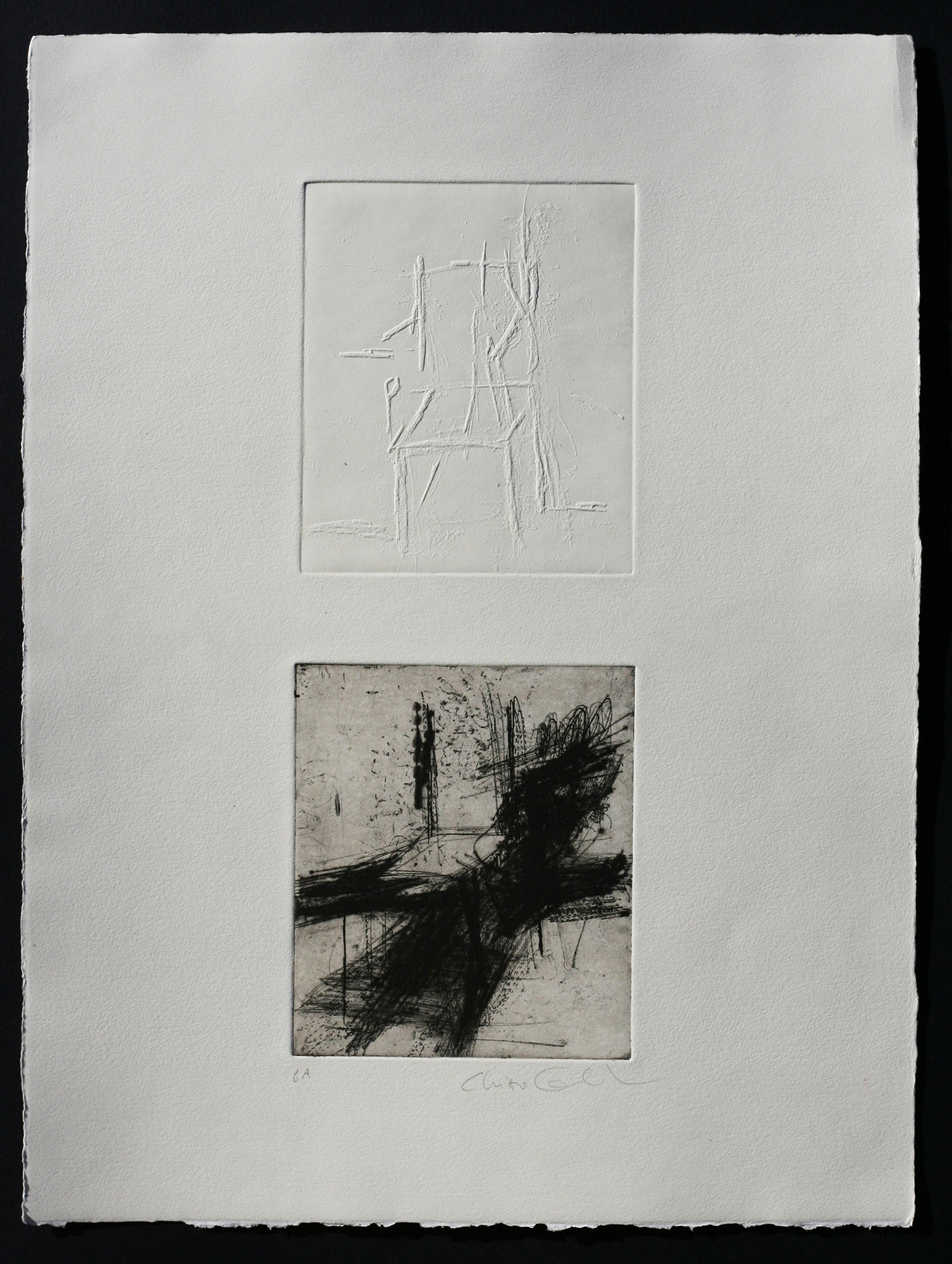

Sedia elettrica, 2000 – Aquaforte, drypoint

Nature, and more generally the ecological theme, returns often in your works. Looking at your works one would say that Nature is sometimes something that saves, or impassively observes Humanity making mistakes without interfering, strong in the knowledge that somehow its cycles will overcome any current contingency. What is your relationship with the natural element?

I started building sculptures or three-dimensional elements of my paintings with willow branches that farmers use for bindings, fascinated by their flexibility and linearity. As an artist, I was then very impressed by V. Fagone’s monographic course on Art and Nature during my senior year at the Academy, and I always follow with interest projects such as Arte Sella and artists who engage with the grandeur of natural spaces.

For me, Nature is the amniotic fluid in which we are immersed. We need Nature, not the other way around. The defence of nature is the defence of humanity at its highest level. The attitude of destroying nature is related to the destruction of man. The birch forest in the work cited above is a kind of invitation to reflect on this.

On the occasion of the felling of 150 trees in a historic part of Monza Park to widen the racetrack, I made the installation “metamorphosis of a park” in 1996 in collaboration with two photographer friends. It somewhat saddens me to see that most people, at least in my city, take the existence of a green lung for granted and conversely get excited about those gray lungs that inhabit it like cancer.

Since your time at the Academy, you have dwelt on “sign as a thin boundary between painting and sculpture.” In your works, different languages and techniques blend in an exchange that sees polymateric paintings punched, hammered, sculpted and conversely two-dimensional, narrative, linear sculptures. What tool does the Sign become in your hands when creating a work?

In all my artistic work, there is a clear interest in the sign whether it is the pencil line, the ink trace, of charcoal, the engraved one or the three-dimensional one of weaving waste threads, willow suckers, iron wire etc. I investigated theoretically this space of art starting from the Academy of Fine Arts thesis “Gastone Novelli in Dialogue with Klee.” The interest in the sign has to do with the discourse of lightness, the fascination of childish babbling, the balance between empty and full, and the ambiguity of the perception of space and its depth.

In this sense, although it is difficult to see as my work is anything but mathematically organized and programmed, Gianni Colombo’s academy lectures opened my mind and fascinated me.

Fiori, 2021- Aluminium fired, installation at Belvedere della Villa Reale in Monza

Your works originate from a series of reflections often triggered by reading, watching films, and observing other works of art. Your artistic universe is dotted with music, quotations, homages, and references. Your works almost seem to be useful means of expressing a stream of consciousness that unites these contents and almost creates a conceptual map of them. How do these connections come about? Are they intentional or an expression of a spontaneous mental and sentimental ferment?

I consider myself to be quite ignorant in the field of music, my listening is mostly casual and usually in the background of other activities. Sometimes, however, I have found tracks particularly effective in relation to my work. Such is the case with Monostress 225 by Les Tambours du Bronx, a French group of percussionists who recycle large empty oil barrels as drums. I used their music for the exhibition “Hanged” – curated by A. Von Furstenberg, Milan, 1996 – because this sound, between the tribal and the industrial, was effective in relation to the theme of the installation, as it was the story of the nine Ogoni activists, hanged in Nigeria in 1995, who were protesting against the massive pollution and exploitation of the territory by the oil industries.

An author which I particularly love is Fabrizio de Andrè. The installation “the majority stands” derives its title from “Smisurata preghiera” (“Immeasurable prayer”) (Anime salve, 1996). The harmony with the singer-songwriter from Genova lies in the pungent delicacy with which he treats people and situations. Inspired by the absent and expressionless faces of passengers on the subway, the work consists of a multitude of small paintings of faces and heads in wire scattered on the wall, a crowd, indeed the majority, of static people who see existence passively passing by highlighting a sense of deep incommunicability.

Different from music, I really love poetry and art cinema in particular. I consider cinema to be the highest art form. It only has the defect that it lasts a limited time and cannot be put up on the wall or accompany you in your daily existence. The time of enjoyment is decided by cinema while that of painting or sculpture is decided by the viewer.

Of Tarkowskji I love the films, the polaroids he took in Italy, and his theoretical text “sculpting time.”

I like the written word that I have repeatedly translated into visual language as in the sculpture made of metal elements and willows “Soldiers” (transcription of Ungaretti’s poem of the same name “Si sta come d’autunno sugli alberi le foglie”).

Finally, the relationship between painting and sculpture is fundamental. Klee, Kiefer, Bourgeois, Kiki Smith are the artists I am currently most interested in besides Titian, Rembrandt, and Tintoretto. I like to make tributes to artists who have influenced me, as moreover did painters far more famous than me (I am thinking of V. Gogh’s drawings of Millet’s) and in this sense, I have in mind a project on Gastone Novelli, the artist on whom I did my thesis at the Academy of Fine Arts.