WINNER OF THE COMEL AWARD 2015

Interview to Silva Cavalli Felci

by Rosa Manauzzi

She was born in 1935 in Bellinzona (CH, Italy). After high school she spent two years in London where she followed courses in drawing and stage design. She completed her studies at the ‘Accademia Carrara di Belle Arti’ in Bergamo. Since 1997 she has directed an Expressive Arts workshop with attention being paid to research and the voice of discomfort. She lives and works in Bergamo. In 2014 she published the monograph ‘La vita è insufficiente’ [Life is insufficient] by Paola Tognon (Lubrina Ed., Bergamo). In march 2015 the book ‘Il mito di Inanna. Amore e potere al femminile nel patriarcato’ was published, edited by Sonia Giorgi (Aracne Editrice, Roma) with art images by Silvia Cavalli Felci and poems by Pasqua Teora.

Let’s start to know you better through your training path. In the ’50s you chose London as a place of art – a very unusual choice for a woman, by the way: you abandoned your land and went to study and live abroad. Why did you prefer it to other cities?

London was an obvious choice for me. The provincial town in which I had lived my youth along with family circumstances had not granted me, after high school, to follow my inclinations. London was crucial in my very unusual formation as it allowed me to indulge my desire for knowledge through the assiduous attendance of museums, concerts and performances of a high standard and to attend the St. Martin’s School course of Arts and Stage Design. If possible, I might have chosen a more direct route: Milan and the Accademia di Brera.

The Carrara Academy of Fine Arts in Bergamo, where you completed your studies, brought you back to a more traditionalist environment. Was it the inspirational place which triggered your desire to experiment?

The attendance of the Accademia Carrara made me feel empowered and enabled me to an artistic practice that has become an integral part of my life. I owe this to the Maestro Trento Longaretti and his appreciation for my work. Then, “the desire to experiment,” as you call it, continued inexorably its course without interruption.

What are the materials and techniques that you privilege and how have they changed over time? And what are the works you love the most and that best represent the various stages of your career so far?

The choice of materials and techniques is always functional to the expression of thought and therefore varies in the different phases of my work. I have no work that I love more than others: once they are born and survive I love them. It is something similar to the bond between a mother and her children.

I could pick a few, emblematic for each phase, as I tried to do in the monograph ‘Life is insufficient.’ [‘La vita è insufficiente’]

Orfeo

Your works are, in some way, carved, engraved, almost wounded, but finally consolidated and strengthened. It almost seems as though you bring out their soul in an initiation rite, after which the soul itself can fall into the matter again and support it strongly. The material thus comes to life in the eyes of the viewer.

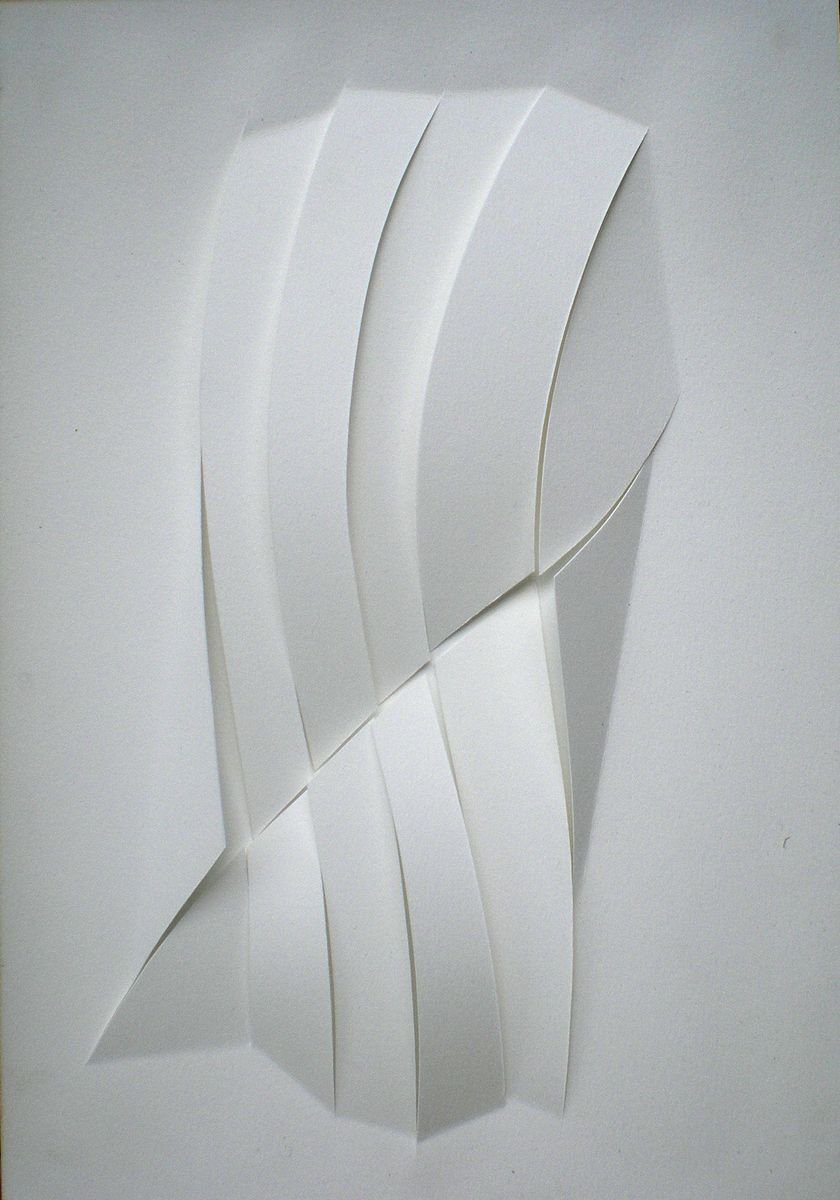

I think my work is the result of my temperament, my need to learn more about myself, about the reality and, perhaps, the utopian ability to transform it. Watercolors and pastels of the late 70s – early 80s represent the inner energy, vibrations, instinctual shots, knots of thought-feeling-emotion, made using the tools very quickly and rhythmically. At a later stage, I used abandoned woods, barks, ash, sand, tar-like as underground sap and fire as an agent of transmutation: subjects whose life was suspended, but for me full of potential energy. Hereafter, my work becomes more lean and focused. My most recent works are sculptures made of composite materials, stainless steel, and aluminum mirrors, contemporary to cuts on small paper. The wound, the tear (the unit lost or perhaps the hope of meeting again), cutting volumes as “exploded” and then reassembled in a new equilibrium are recurring themes in my work.

You’ve recently won the fourth edition of the international COMEL Award “Vanna Migliorin” – Contemporary Art. “Danza rossa” (Red Dance), the work chosen by the jury was also rated among the most voted by the public. Can you tell us the origin of this work?

The work “Danza rossa”, specifically created for the COMEL Award, is the latest in a cycle of works started in 2013. A summary of the work is carried out at first with three-dimensional drawings on white, black and sometimes red paper, in which the pencil has been replaced with a blade whose cuts do not admit repentances. Subsequently, the paper was replaced with aluminum plates, which granted the use of a larger size. In this case, the cuts are engraved with the laser while the movement in leavening of the various parts is performed manually thanks to the flexibility and strength of aluminum itself. For the work intended for the Comel Award, I chose the color red in its positive symbolism, looking for that balance and harmony in the signs, perhaps still possible, or at least desirable in opposition to the hectic time in which we live.

Your book “La vita è insufficiente” (Lubrina Editore, Alessandria, 2014) is a collection of your artistic experiences, which often implied sharing with writers, poets, researchers, people who deal with other fields of study. Among others: the poets Rina Sara Virgillito, Sergio Romanelli and Adriano Piccardi. It is not easy to find the right creative empathy. How are your contributions originated?

My interest in other forms of art and knowledge more broadly favored the friendship with people whose creativity and deep thinking have nurtured and accompanied my creative path. The idea of creating a joint work blossoms almost always spontaneously. As for the poets, sometimes we started from work to poetry, sometimes from poetry to work. The ballet ‘La rosa del deserto’ [The Desert Rose] of which I have designed the subject, the scenery and costumes, was instead set to music by Maestro Massimiliano Messieri after several meetings and depth analysis.

Among your creatures there has also been a cultural association: “Polyhedron, practise and images of the psyche”, along with the Jungian psychoanalyst Sonia Giorgi. What was your goal? How was Sand Therapy applied in the laboratories of expressive activities that you led?

Yes, a very much loved creature, born after a long gestation, but one that lasted just a few years, due to organizational difficulties and hardships. ‘Polyhedron’ was the realization of a desire of mine and of Sonia Giorgi, a Jungian psychotherapist, a longtime friend. It was a desire gradually transformed into a dense and complex program. The cultural association ‘Poliedro’ (Polyhedron) intended to offer an open space where people with common interests in the field of culture, art and of psychological inquiry could relate; a place that accosted moments of discussion and reflection, moments of production and testing of the symbolic world through expressive activity and therapeutic art, retracing the myth and literature in key symbol and soul searching. The sand play was used in various laboratories as a means of expression. It was complementary to various other modes (clay, drawing, collage, theatre, etc.). In numerous meetings, some topic issues were discussed, such as the question of male and female, man’s relationship with supernatural forces, suffering, art as an expression of inner paths; six meetings were devoted to the characters of the classic tragedy, Antigone, Electra, Oedipus and Jocasta.

Movimento carta

In March, the book ‘Il mito di Inanna. Amore e potere al femminile nel patriarcato’ [‘The myth of Inanna. Love and female power in patriarchy’] came out, written by Sonia Giorgi (Aracne Editrice, Rome) with your own images of art and poems by Pasqua Teora. You had already worked on this myth in ‘The journey of Inanna, Queen of the Worlds’, in your expressive workshops. The myth, as transmission of exemplary stories, seems to fascinate you in a special way and it is intertwined with your extensive research on women. What can Inanna, the Phoenix and the woman of antiquity teach us?

My interest in Inanna goes back to the ’80s, when a friend suggested me to read: ‘The Sumerians: Their History, Culture and Character’ by Diane Wolkstein and Noah Kramer and ‘The Great Goddess – The journey of Inanna Queen of the Worlds’ by Sylvia Brinton Perera. I realized then that this goddess could be of great help to us as women of the second and third millennium. The problems against which we were fighting were similar: as daughters of patriarchy had to recover energy that were buried in us, energies that we were not been able to protect. Inanna taught us the way to go to recover them, to understand our distress, to bring us closer to self-awareness, not without difficulties, as told by her journey to the underworld. I felt a strong desire to share my enthusiasm for this myth with others, and I thought of proposing a deep study with ten group meetings in my lab of expressive activities: reading verses and giving shape to our own feelings with the materials and available techniques. It was an exciting experience.

In your rich curriculum there are also experiences as screenwriter, set designer and costume designer. A deep-rooted presence in the theater. Tell us about that…

This is an activity that is limited to an amateur level, but that gave me a lot of joy and allowed me to enter other areas that I loved. With my friend Enrico Asti, attorney and “actor manqué”, intellectual, expert on music and insatiable reader, we spent our time choosing a text, then we reduced it for two voices and we tested the staged reading. I had the task to design and build sets and costumes with limited means and an improvised space. Of course, in our varied repertoire we could not keep apart the Sumerian poem ‘The journey of Inanna’, which was also represented at the site of the archaeological museum of Bergamo. What do Inanna and the Phoenix teach us? They are both myths of death and rebirth. It is embarking on a symbolic journey into the deep, to self-knowledge, a journey that involves fatigue and pain, but from which we go back to the light and to desire with renewed force.

What advice would you give to a young person that has just started his career as an artist?

In my opinion, you do not have to give advice. If young people feel the “call”, they must look within themselves without expecting answers. Becoming an artist involves sacrifice, dedication, sacrifice and, above all, the passion, which legitimizes the vocation to the world and themselves, regardless of success. “The youth in painting is gained slowly, it will be given as a reward to the deserving old”1 (Jean Bazaine). Allow me to substitute the word “painting” with the word “art”, as an expression of the spirit.

Your next project?

Rather than a project I’ve got a wish or a hope: the construction stage of my ballet “The desert rose”.